Two weeks into the Apple v. Samsung trial, there have been some very interesting stories to come out. From lawyers being scolded for making press releases and not having their court admission ducks in a row to evidentiary rulings on the admissibility of evidence of independent development. These stories are interesting in their own right, but I think it would be helpful to see how they relate to the endgame of the litigation. That endgame is actually spelled out, from Apple’s point of view, in the first document filed in the case: the complaint.

Complaints are the legal pleadings that start the ball rolling in a case and can provide a basis for understanding why the parties do what they do. For example, in an earlier post I wrote why certain evidence of independent development was not admitted, much to the chagrin of some tech bloggers and the general public. Unfortunately, I haven’t see a simple dissection of the claims in the complaint.

With that in mind, I’m going to go through the claims in the complaint that relate to IP issues. I’ll leave the other state claims, like unjust enrichment, aside as the facts needed to prove them are similar to the IP issues, but they are likely being plead to provide different damages theories. In this post, I’ll focus on trade dress infringement.

Trade Dress Infringement

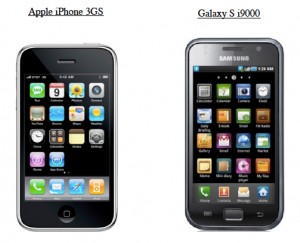

There are two types of protectable trade dress: product configuration (which protects the product itself), and product packaging. Apple describes it’s iPhone product configuration as it’s “distinctive shape and appearance — a flat rectangular shape with rounded corners, a metallic edge, a large display screen bordered at the top and bottom with substantial black segments, and a selection of colorful square icons with rounded corners that mirror the rounded corners of the iPhone itself, and which are the embodiment of Apple’s innovative iPhone user interface.”

There are two types of protectable trade dress: product configuration (which protects the product itself), and product packaging. Apple describes it’s iPhone product configuration as it’s “distinctive shape and appearance — a flat rectangular shape with rounded corners, a metallic edge, a large display screen bordered at the top and bottom with substantial black segments, and a selection of colorful square icons with rounded corners that mirror the rounded corners of the iPhone itself, and which are the embodiment of Apple’s innovative iPhone user interface.”

Apple also alleges that the product packaging of the Samsung GalaxyS infringes the packaging trade dress of the iPhone. Below are the images provided in the complaint.

are the images provided in the complaint.

Product packaging is generally more susceptible to trade dress protection than product configuration. This is because physical attributes of a product are often functional and functional aspects are not protectable as trade dress. To limit the scope of product configuration trade dress protection, it is only available for product designs that have become become distinctive as a result of an acquired secondary meaning. That is, the design must evoke, in the mind of the consumer, a particular source of the product.

Product packaging is generally more susceptible to trade dress protection than product configuration. This is because physical attributes of a product are often functional and functional aspects are not protectable as trade dress. To limit the scope of product configuration trade dress protection, it is only available for product designs that have become become distinctive as a result of an acquired secondary meaning. That is, the design must evoke, in the mind of the consumer, a particular source of the product.

There are also two statutory mechanisms for recover for trade dress infringement. The Lanham act codified common law principles of trademark and unfair competition and allows for federal suits in cases involving unregistered trade dress. The Act also allows for registered trade dress. The legal difference is that a registered trade dress is likely entitled to some presumption of protectability, but the damages and equitable relief available are roughly the same.

However, having a protectable trade dress isn’t enough. Apple will have to show that Samsung’s product configuration and/or packaging are confusingly similar to Apple’s. It’s important to note that the gauge for confusion is the relevant consumer. While tech bloggers may not confuse the two, the question really is if a typical consumer would.

Next up, I will provide a little background for the utility and design patent infringement allegations in Apple’s complaint.