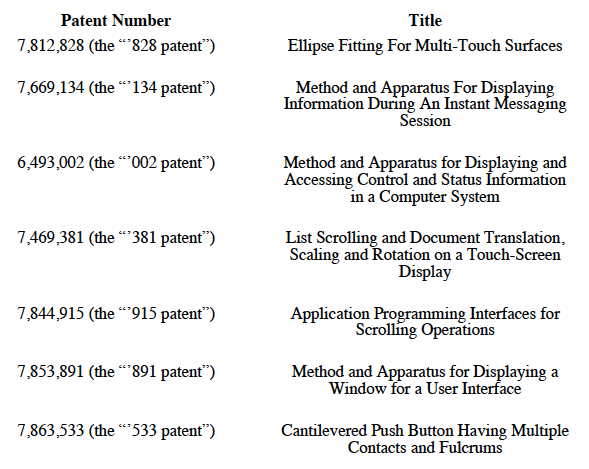

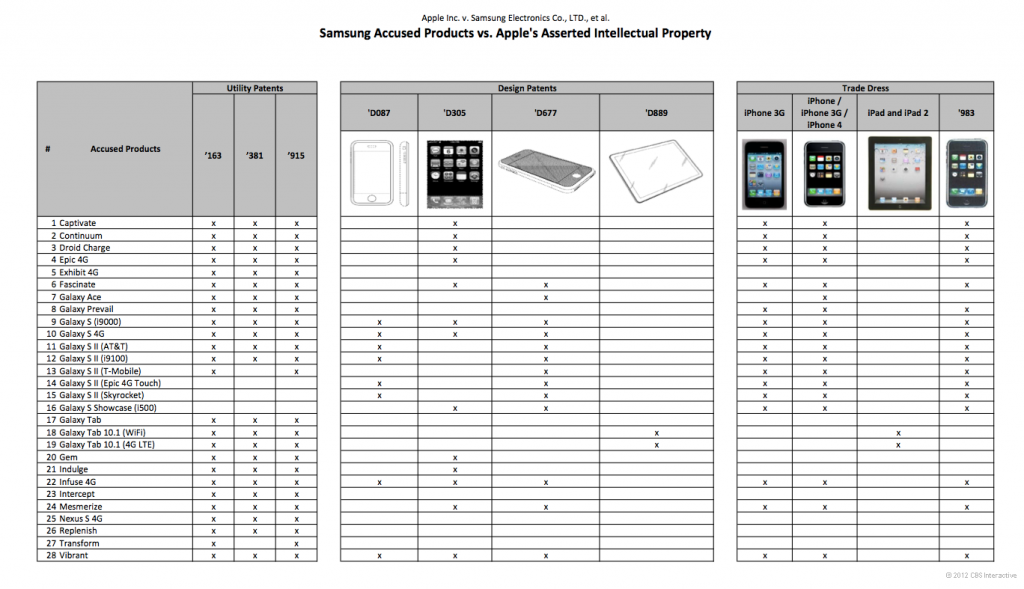

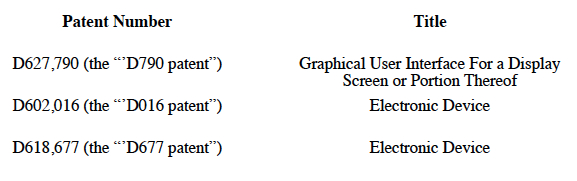

There are some very good summaries of the Jury verdict, and there is also a lot of speculation about what happens now that the jury found various Samsung patents infringe Apples patents and trade dress. The jury’s verdict form shows how they answered the various IP claims. In summary, all of Apple’s and Samsung’s patents (utility and design) were found valid. However, none of Samsung’s patents were infringed and the vast majority of Apples were. However, the jury form also gives a some indications of what may happen next in this case.

There are some very good summaries of the Jury verdict, and there is also a lot of speculation about what happens now that the jury found various Samsung patents infringe Apples patents and trade dress. The jury’s verdict form shows how they answered the various IP claims. In summary, all of Apple’s and Samsung’s patents (utility and design) were found valid. However, none of Samsung’s patents were infringed and the vast majority of Apples were. However, the jury form also gives a some indications of what may happen next in this case.

While a lot will be written in the next week on pending appeals and cross appeals, motions for judgement notwithstanding the verdict (JNOV), and other post trial maneuvers, Judge Koh will also have to decide if she will award an injunction preventing future sales and imports of the infringing products. Injunctions are imposed as an equitable remedy by the judge, not the jury. In deciding whether or not to grant an injunction in patent cases, federal judges must apply the eBay factors, named for the 2006 eBay v. MercExchange case in which the Supreme Court clarified the factors that must be weighed. Those factors that a plaintiff must demonstrate include:

(1) that it has suffered an irreparable injury;

(2) that remedies available at law, such as monetary damages, are inadequate to compensate for that injury;

(3) that, considering the balance of hardships between the plaintiff and defendant, a remedy in equity is warranted; and

(4) that the public interest would not be disserved by a permanent injunction.

Since that case, courts have been more reluctant to grant permanent injunctions at the end of a patent trial. One reason cited for the decline in injunctions is that the presumption of irreparable harm is dead. This case is a bit different though.

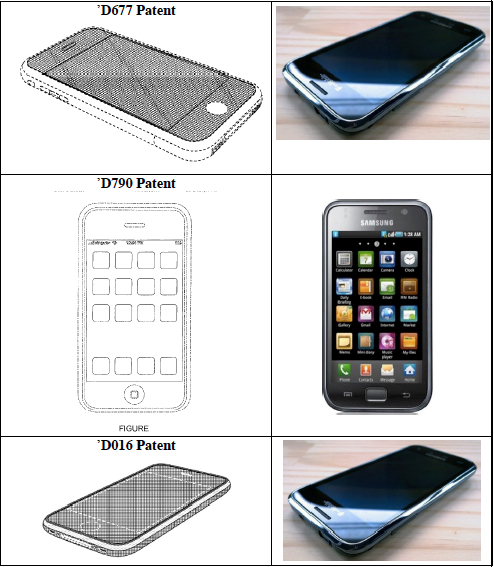

In addition to the patents infringed, Samsung was found to both infringe and dilute Apples iPhone trade dress (both registered and unregistered). The strength of Apple’s trade dress is in its distinctiveness and Apple’s continued use of it. Trade dress protection is only available so long as the trade dress serves as a source identifier for the product. If another manufacturer can sell goods that infringe or dilute Apple’s trade dress going forward, that would likely do irreparable harm to Apples trade dress rights against other parties.

In this case, there is significant overlap between the design patents and Apple’s trade dress. There is even an arguable overlap between the utility patents and trade dress as the rebounding scroll lists covered by some of the utility patents are part of the look and fee of the various iOS devices. In this unique case, Apple is in a position to argue that failing to provide a permanent injunction would pose an irreparable harm to Apples other intellectual property, namely it’s trade dress.

My personal feeling is that Apple has a better than average chance of obtaining a permanent injunction. Whether the rationale behind it will be based solely on the patents, trade dress, or a combination where the various forms of intellectual property reinforce a showing of irreparable harm will be interesting to see. Keep in mind, that while it isn’t a slam dunk, Judge Koh did show a willingness to impose a preliminary injunction early in the case.

As it stands now, Apple will file its motion and brief on August 29, Samsung will reply on or before September 12 (the rumored launch date of the iPhone 5), and a hearing before Judge Koh will be held on September 20.

UPDATED: Judge Koh, has scheduled the hearing for Decmeber 6.