Over the course of the last week, I’ve come across two blog posts, via my twitter feed, that show opposite views on patent litigation. The first takes the position that patent troll litigation is rampant and stifling innovation, especially for startups. The title, “Numbers Don’t Lie: Patent Trolls are a Plague” sums up the author’s position nicely. However, the piece doesn’t paint a very comprehensive picture.

The numbers referred to are those based on a survey by Colleen Chien of Santa Clara University – School of Law. Prof. Chien notes that 40% of respondents stated that troll activities had had a significant impact on the startup’s operations. However, the fact that patents are asserted against emerging businesses more often than others shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, if a company is arguably infringing a patent as part of its core business, it would be expected that the issue would come up earlier in the company life cycle. These numbers could be skewed relative to the economy as a whole.

The second article takes another tack as you can see from the equally suggestive title, “The ‘Patent Litigation Explosion’ Canard.” As you can guess, the author, Prof. Adam Mossoff, disagrees with the idea that there is a “Patent Litigation Explosion” going on. This piece discusses patent litigation rates (measured as a percentage of issued patents litigated). From 1790 to 1860 the rate averages 1.65%. From 2000-2009, it was 1.5%.

I’m inclined to think the litigation rates over time to be a better indicator of the growth of patent litigation than a survey of startups. To be honest, I was skeptical of the litigation rates, not that they are inaccurate, but they may not be very meaningful if the number of patents issued relative to GDP has gone up. My assumption was that the number of patents issued per billion dollars of GDP would have grown and that the a constant litigation rate would actually mean an overall increase in patent litigation relative to GDP. That assumption was wrong.

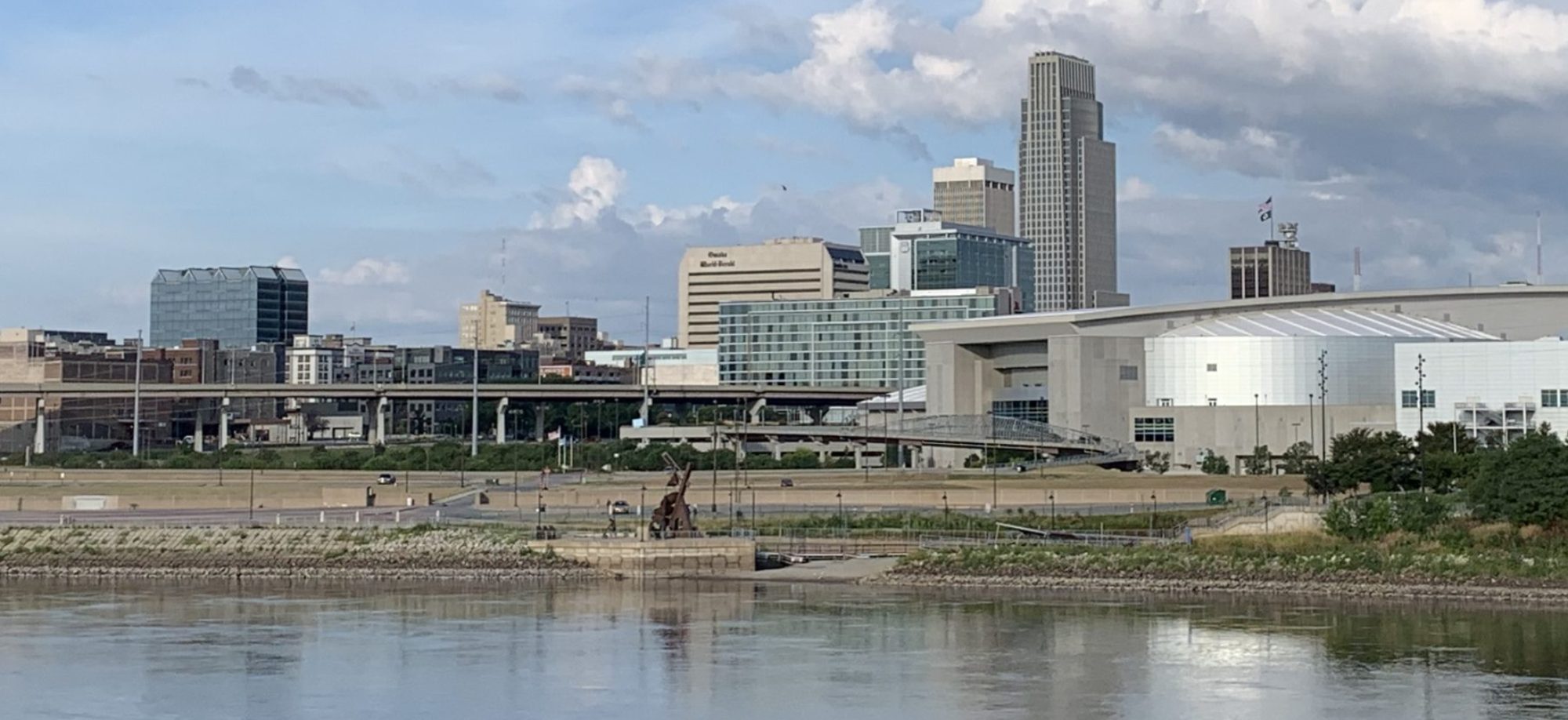

First I looked to the USPTO data regarding patents issued. Here is a chart for patents issued each year from 1963 to 2011.

The “ups” and “downs” unsurprisingly correlate to the general state of the economy as fewer patents issue during and after economic downturns. However, I was interested in the number of patents issued per billion dollars in GDP. I used real GDP data (GDP adjusted for inflation) and the number of utility patents issued for each year from 1963 to 2011. So, I simply divided the number of patents issued in a given year by the inflation adjusted GDP that year. The following chart shows what I found:

While there is a lot of variation, the overall trend appears relatively flat. The average number of patents issued per billion dollars of GDP from 1963 to 2011 was 13.00, and a significant portion of the last decade was below that. Accordingly, the litigation rates referenced by Prof. Mossoff are informative and it appears that there has not been a significant increase in patent litigation, relative to GDP.

Of course, this is only part of the story. Calculating litigation rates as a function of the number of patents issued in a particular year doesn’t necessarily correlate to the number of patents in force (i.e. issued and with all relevant maintenance fees paid that have not yet expired) for that year, but it is, perhaps, a leading indicator of the number of patents that will be in-force in years to come. Such a calculation, however, is easier to make and is likely a reasonable starting point.

Another issue is that these numbers doesn’t tell us the economic impact of patent litigation. While the number of cases relative to GDP is steady, the average price tag (damages, attorney’s fees, etc) associated with a patent litigation may have grown relative to GDP, or there may have been a significant increase in licenses entered before a complaint is filed. However, I haven’t seen any data to show that either of those things has happened.

Of course, using the term “troll” in connection with a patent asserting party tells us a lot about the party’s position. However asserting a patent is not regarded as a bad thing in most circles, especially if the asserter is a big operation in a particular field. The actual distinction to be made is that the patent asserter is or is not in a business to which the patent relates. Now, in our country historically, that was not an issue because as a “developed” country we were immune to any significant effect of patent assertion because there was such robust growth in industry and there was always a route to non-infringing competition. But, in “undeveloped” or “developing” countries, the law usually set out rules for mandatory licensing. The rationale was that the struggle to develop a strong industrial setting needed to have patents, but not allow them to be used to shut down production of a product. Interestingly, we, the USA are now moving toward mandatory licensing, which tells us that we are no longer so robust in industrial growth that we are immune to an injunction against infringing a patent. The conclusion is that our industrial status is declining.

Another point about “patent trolls”, aside from the Goebbels-Rove propaganda effect, is that they don’t want to shut anyone down, all they want is a royalty. And the reason there is a lot of litigation isn’t because they want to sue, but because they have to. The opposition feels offended by paying a royalty to a non-practicing entity. Why, its just a propaganda scheme, there is no reason to conclude that a patent should be more or less valuable based on who owns it- the value is measured by who want to use the invention. The bottom line is that the “big guys” don’t like little patent owners to interfere, with “real” industry. Notably the “troll” is an entity that takes over from an individual who of course could not afford to maintain a patent law suit.

I agree about the language. “Troll” is a term I don’t typically care for in describing NPEs. One thing that people also ignore is the impact of the secondary market for patents created by NPEs. This arguably benefits small entities and inventors who, as you said, could not afford to maintain a patent law suit.

As it happens, I am chanirig a session at the PIUG annual meeting in Baltimore today, and one of my speakers is from INPI. An early sight of her presentation materials suggests an alternative possible explanation.Brazil was allowed to implement a pipeline protection system in the years immediately following WTO entry. Once the new law was fully implemented on 14 May 1997 the pipeline closed.Article 230 of the new law required ‘pipeline’ applicants to indicate, in their filing petition, the date of the first application made (i.e. the priority date claimed for the Brazilian application), with the further condition that the corresponding foreign application would have to issue as a patent. In the absence of the corresponding foreign patent, no patent rights would be granted in Brazil. The patent eventually granted in Brazilwould be assured a term equal to (but not longer than) the remaining term of protection granted in the country where the application was first filed.If the application referred to in this suit falls under the transitional provisions of this part of the Act, it is feasible that the court could have held that the Brazilian patent must expire on the same date as the British patent from which it claims priority.This comment is subject to verification by my speaker, who is currently stranded somewhere between Sao Paulo, Chicago or Baltimore. If I discover more, I will attempt to post an update.

As much as I think I’m against patnntieg genes, DNA, humans, etc. in the first place, I think that mostly what’s going on is marketing. For better or for worse, in newsworthy issues like this, that will involve spinning the issues in the public sphere so that it piques the attention of more people. Bio patents are a pretty touchy issue, and this is another perspective. I’m not surprised, or offended by this.

Jennifer,

I’m so sorry I didn’t see this comment before. I think the media does a disservice by blowing these things out of proportion. Since your comment, the Supreme Court has ruled on claims to isolated DNA and held them, in their natural sequences, to be unpatentable. The ensuing frenzy from biotech made it sound like they would go out of business, but, alas, life goes on.

The same is true with the issue of “patent trolls.” I don’t think they are the scourge they are made out to be, but there are a few bad actors. What we read in the press are anecdotes of businesses that are targeted by these bad actors, not statistics that show the overall situation. That doesn’t mean these situations don’t suck for the businesses involved, but ignoring the bigger picture just leads to hasty policy decisions.