There has been a lot of discussion of a patent issued to Apple last week. U.S. Patent 8,223,134, issued to Apple on July 17, 2012, and has been called everything from an “Android Killer” to something all other smartphone makers should fear. This patent relates to the the user interface of various iOS devices. However, many people don’t realize how the exclusionary power of a patent is defined. Only the claims, those numbered paragraphs at the end of the patent, define what is protected.

There has been a lot of discussion of a patent issued to Apple last week. U.S. Patent 8,223,134, issued to Apple on July 17, 2012, and has been called everything from an “Android Killer” to something all other smartphone makers should fear. This patent relates to the the user interface of various iOS devices. However, many people don’t realize how the exclusionary power of a patent is defined. Only the claims, those numbered paragraphs at the end of the patent, define what is protected.

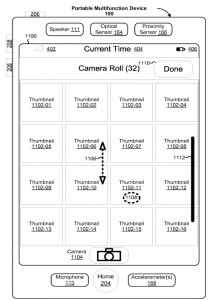

Some have characterized the claims of the ‘134 patent a overly broad, but take a look at the broadest device claim:

A portable multifunction device, comprising:

a touch screen display;

one or more processors;

memory; and

one or more programs,

wherein the one or more programs are stored in the memory and configured to be executed by the one or more processors,

the one or more programs including instructions for: displaying a portion of an electronic document on the touch screen display, wherein the displayed portion of the electronic document has a vertical position in the electronic document;

displaying a vertical bar on top of the displayed portion of the electronic document, the vertical bar displayed proximate to a vertical edge of the displayed portion of the electronic document,

wherein: the vertical bar has a vertical position on top of the displayed portion of the electronic document that corresponds to the vertical position in the electronic document of the displayed portion of the electronic document; and

the vertical bar is not a scroll bar;

detecting a movement of an object in a direction on the displayed portion of the electronic document;

in response to detecting the movement: scrolling the electronic document displayed on the touch screen display in the direction of movement of the object so that a new portion of the electronic document is displayed,

moving the vertical bar to a new vertical position such that the new vertical position corresponds to the vertical position in the electronic document of the displayed new portion of the electronic document, and

maintaining the vertical bar proximate to the vertical edge of the displayed portion of the electronic document; and

in response to a predetermined condition being met, ceasing to display the vertical bar while continuing to display the displayed portion of the electronic document, wherein the displayed portion of the electronic document has a vertical extent that is less than a vertical extent of the electronic document.

The claims are actually fairly narrowly tailored to cover the iPhone and other devices non-scroll bar on list and document displays. The vertical bar must not be a scroll bar; it mus be imposed over the image being displayed; it must change its position as the image is moved vertically by the user (who must be moving the image via natural scrolling); the vertical bar must stop being displayed, i.e., after a preset time with no movement on the screen. All of these conditions must be met by another device’s UI before it can infringe this claim. Omitting any of them will avoid literal infringement.

I realize it’s not as exciting as claiming that the patent will shut down all competition in smartphones, but it won’t.

I personally think this shows the value of patents in this area. What Apple has done with these claims is to provide itself with some protection against direct copying of these features of its UI. Other companies still have a lot of room to develop competing systems and devices, even better ones. These patents help prevent knockoffs from eliminating the incentive to create while still leaving the door open to new competition. In the end, consumers win.

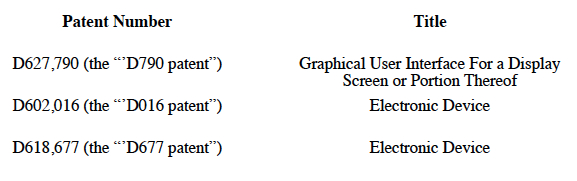

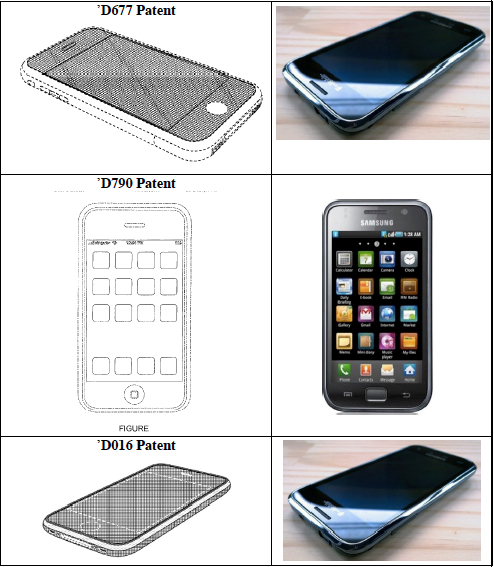

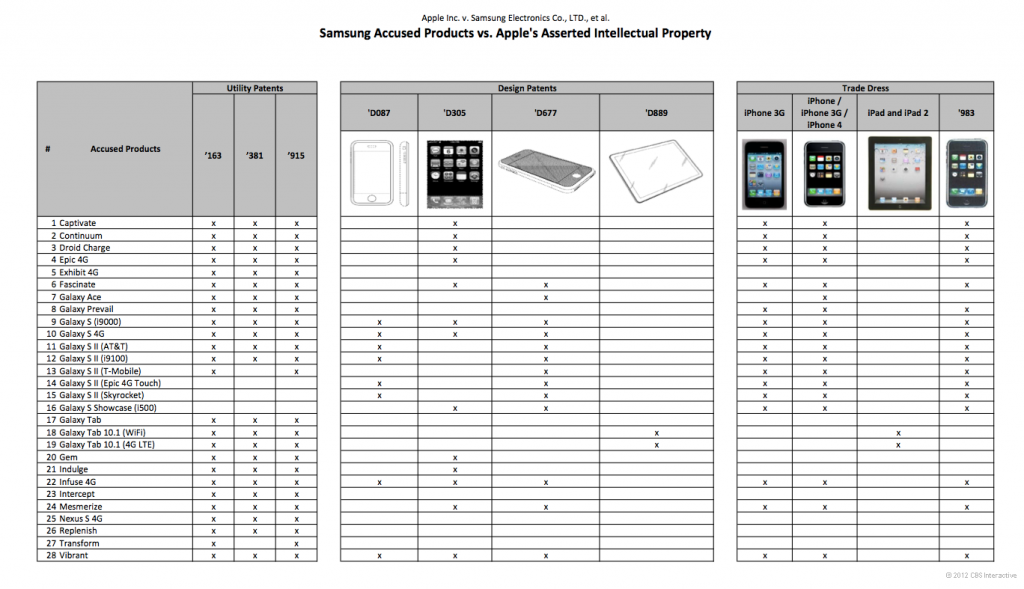

With over a year of pretrial motions, hearings, and orders, the list of asserted patents has been whittled down to three: the ‘163, ‘381, and ‘915 patents. These patents relate to various features of the iOS UI including pinch to zoom, rebounding list scrolling, and rebounding scrolling on the home screen, respectively. These patents are not so broad as to block any competing smartphone. If fact, earlier versions of the Android operating system did not include rebounding scrolling and

With over a year of pretrial motions, hearings, and orders, the list of asserted patents has been whittled down to three: the ‘163, ‘381, and ‘915 patents. These patents relate to various features of the iOS UI including pinch to zoom, rebounding list scrolling, and rebounding scrolling on the home screen, respectively. These patents are not so broad as to block any competing smartphone. If fact, earlier versions of the Android operating system did not include rebounding scrolling and Samsung is arguing that the patents are not valid because the features claimed were already known when Apple filed its patent applications.

Samsung is arguing that the patents are not valid because the features claimed were already known when Apple filed its patent applications.